Exploring the Cybersecurity Domains: A Comprehensive Guide

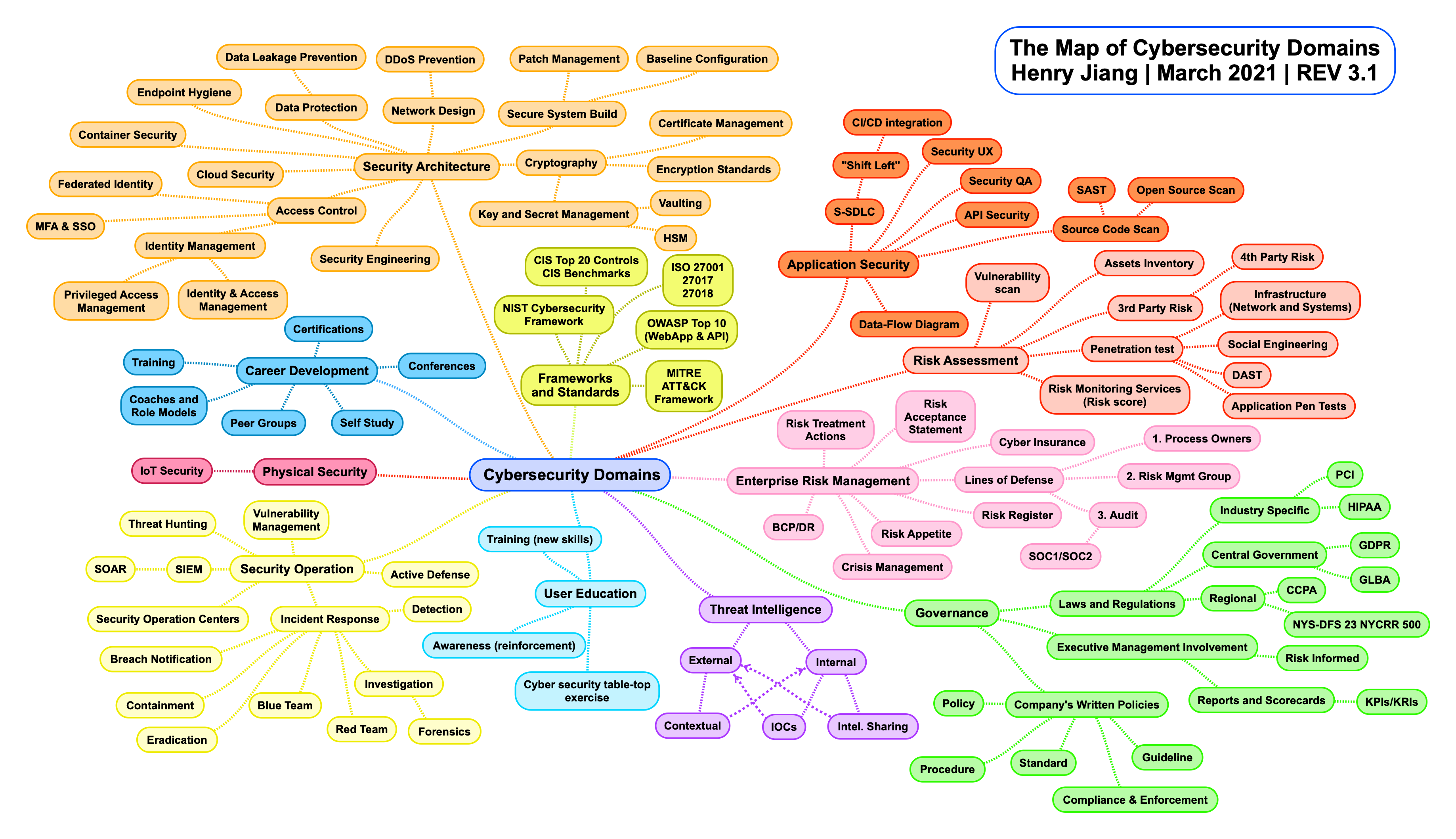

Cybersecurity is an ever-evolving field that encompasses various domains, each vital to understanding and protecting the cyber ecosystem. Henry Jiang, a prominent figure in cybersecurity, has mapped out several of these domains, providing a framework for professionals and enthusiasts alike to navigate this complex landscape. In this blog post, we'll explore these domains extensively, supplementing Jiang's framework with additional insights and details to enrich your understanding of cybersecurity's multifaceted nature.

What Are Cybersecurity Domains?

Before diving into specifics, let's define what we mean by "cybersecurity domains." These domains are distinct areas of expertise within the realm of cybersecurity, each focusing on different aspects of safeguarding information systems and data. They range from managing the risks posed by cyber threats to ensuring compliance with regulations and standards.

The Core Cybersecurity Domains

According to Henry Jiang and supplemented with industry knowledge, the core cybersecurity domains include but aren't limited to the following:

Security Architecture in Cybersecurity

Security architecture forms the bedrock of an organization's cybersecurity defenses. It is a holistic blueprint that outlines how cybersecurity measures are integrated within the information technology environment to safeguard data and assets from cyber threats. Taking cues from Henry Jiang's Map of Cybersecurity Domains, let’s examine the critical elements of security architecture.

Data Protection

At the heart of security architecture is data protection. This involves implementing measures to ensure that data—be it stored, in transit, or in use—is shielded against unauthorized access and leaks. Data protection strategies might include:

- Data Encryption: Ensuring data is unreadable without proper authorization or keys.

- Data Masking: Hiding sensitive information within a dataset to protect it during use in non-secure environments.

- Backup and Recovery: Regularly backing up data and having robust recovery plans to prevent data loss.

The right data protection protocols help maintain data integrity and confidentiality, which are crucial for trust and compliance.

Security Engineering

Security engineering is about designing systems that are inherently secure. This entails:

- Threat Modeling: Identifying assets, vulnerabilities, threats, and countermeasures.

- Secure Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC): Integrating security practices at every phase of software development.

- Automated Security Scanning: Using tools to regularly scan code and infrastructure for vulnerabilities.

By baking security into the design process, organizations can preemptively repel threats rather than just reacting to breaches.

Secure System Build

The building and configuring of secure systems ensure that they are safe from the outset. It includes:

- Default Security Settings: Implementing secure defaults to prevent inadvertent security lapses.

- System Hardening: Removing unnecessary services and access points that could be exploited.

- Patch Management: Keeping software up-to-date with the latest security patches and updates.

A securely built system reduces the number of exploitable entry points for a potential attacker.

Access Control

Access control is a fundamental aspect of security architecture that dictates who can access what within a network:

- User Authentication: Verifying the identity of users before granting access.

- Role-Based Access Control (RBAC): Assigning access rights based on user roles to minimize access to sensitive information.

- Least Privilege Principle: Granting users the minimum level of access necessary for their job functions.

These controls help to minimize the risk of unauthorized access to sensitive systems and data.

Container Security

Container security focuses on securing applications and their deployment in the growing use of containerization:

- Container Vulnerability Management: Regularly scanning containers for known vulnerabilities.

- Runtime Protection: Monitoring container activity to detect and respond to threats in real-time.

- Container Isolation: Ensuring that containers are isolated to prevent security issues in one container from affecting others.

Secure container practices are imperative in modern, dynamic environments such as cloud-native applications.

Network Design

The network is the communication backbone of an IT environment, and its design impacts the security posture:

- Network Segmentation: Dividing the network into zones to control traffic flows and reduce the attack surface.

- Firewalls and Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS): Installing barriers and monitoring systems to detect and block malicious traffic.

- VPN and Encryption: Utilizing virtual private networks and encryption to secure data as it travels across the network.

A well-designed network can help thwart cyberattacks and contain any breaches that occur.

Endpoint Hygiene

Endpoints are common targets for attackers. Maintaining endpoint hygiene involves:

- Antivirus and Anti-malware: Protecting endpoints from various types of malicious software.

- Regular Updates: Keeping endpoint systems updated with the latest security patches.

- Device Management: Monitoring and managing devices to ensure compliance with security policies.

Clean and well-managed endpoints are a primary defense against malware and other cyber threats.

Cryptography

Cryptography is the science of securing information through encoding. In cybersecurity, it includes:

- Encryption Algorithms: Use strong and tested algorithms to protect data.

- Key Management: Secure handling of cryptographic keys to prevent unauthorized access to encrypted data.

- Digital Signatures: Authenticating the source and ensuring the integrity of digital communications and transactions.

Robust cryptographic practices are essential for maintaining confidentiality and integrity in digital operations.

Cloud Security

With the shift to cloud computing, cloud security is an essential domain that addresses unique challenges:

- Data Sovereignty: Complying with laws relating to the geographic location of data.

- Identity and Access Management (IAM): Controlling who can access what resources in the cloud.

- Virtualization Security: Protecting the virtualized environments that cloud services operate in.

Effective cloud security practices ensure that assets stored and processed in the cloud remain secure from threats.

By understanding and implementing the components of security architecture, organizations can ensure they have a strong and resilient cybersecurity posture to safeguard

Governance in Cybersecurity

Governance in cybersecurity is an overarching framework that ensures all security efforts align with the organization's objectives and adhere to compliance standards. By governing cybersecurity effectively, an organization can address the risks that come with digital operations and critical data handling. Here's a deeper look into the three essential facets of cybersecurity governance as delineated by Henry Jiang in his Map of Cybersecurity Domains.

Laws and Regulations

Compliance with laws and regulations is paramount in cybersecurity governance. Different industries and regions are subject to various legal requirements that dictate how data should be handled, protected, and reported in case of a breach. Some prominent examples include:

- General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): This European Union regulation imposes strict rules on data protection and privacy for individuals within the EU and the European Economic Area.

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA): A key regulation in the United States that provides data privacy and security provisions for safeguarding medical information.

- Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS): A worldwide standard mandating security measures for organizations that handle credit card transactions.

Organizations must stay abreast of these regulations, not only to avoid penalties but also to maintain consumer trust and prevent reputational damage.

Executive Management Involvement

Cybersecurity is not solely the responsibility of IT departments; it requires active engagement from executive management to succeed. Executives must understand the importance of cybersecurity to ensure adequate resources are allocated to protect the organization's digital assets. Their involvement typically entails:

- Setting the Tone at the Top: Executives must demonstrate that cybersecurity is a priority, integrating it into the corporate culture.

- Decision-Making: Senior leaders should be involved in critical decisions affecting cybersecurity strategies and investments.

- Risk Appetite Definition: Management sets the acceptable level of risk for the organization, which drives the development of cybersecurity policies and procedures.

The active participation of senior management ensures that cybersecurity gets the attention and resources it requires.

Company's Written Policies

Clear, comprehensive, and up-to-date written policies are the backbone of an organization's cybersecurity governance framework. These policies must cover a broad spectrum of activities and standards for behavior regarding technology and data usage, such as:

- Acceptable Use Policy: Defines what is considered acceptable use of the organization's systems and services.

- Information Security Policy: Documents how the organization manages and protects its information assets.

- Incident Response Policy: Details the steps to be taken in the event of a security incident.

- Remote Work Policy: Provides guidelines for employees working remotely to ensure secure access and protection of data outside the company's premises.

Well-documented policies serve as guidelines for employees, helping to prevent mishandling of data and reduce the risk of security incidents. They also play a crucial role in employee training and awareness programs, which are vital to any cybersecurity strategy.

Governance in cybersecurity is a critical domain that underpins the security of an organization's entire IT infrastructure. By comprehensively addressing laws and regulations, involving executive management, and establishing clear written policies, organizations can create a robust foundation to protect their assets in the cybersphere.

Risk Management in Cybersecurity

Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) is a strategic business discipline that addresses the full spectrum of risks a firm faces, including cybersecurity risks. As identified by Henry Jiang, ERM acknowledges that while some risks can be avoided or mitigated, others must be accepted, insured against, or planned for continuity and recovery. Let's delve into the intricate aspects of ERM within the scope of cybersecurity.

Risk Treatment Actions

Risk treatment involves determining what actions will be taken to manage and mitigate risks. Such actions include:

- Avoidance: Ceasing the activities that generate risk.

- Mitigation: Implementing controls to reduce the likelihood or impact of a risk.

- Transfer: Shifting the risk to a third party, such as through outsourcing or insurance.

- Sharing: Engaging in partnerships where risk is shared amongst parties.

Each treatment action is chosen depending on its suitability to manage specific risks within the organization's tolerance levels.

Risk Acceptance Statement

When risks cannot be avoided, some organizations may decide that the best course of action is to knowingly and appropriately accept the risk. The risk acceptance statement is a formal document signed by an authority, stating that they understand the implications of the residual risk and accept the potential outcomes should the risk materialize.

Cyber Insurance

As the cyber threat landscape grows more complex, many organizations are turning to cyber insurance as a way to transfer some of the financial risks. Cyber insurance typically covers costs associated with data breaches, including customer notification, identity protection services for affected customers, and legal fees.

Lines of Defense

The "Three Lines of Defense" model is widely recognized in ERM. The lines include:

- Operational Management: The first line, where risks are owned and managed.

- Risk Management and Compliance Functions: The second line, overseeing risk management and ensuring compliance with policies.

- Internal Audit: The third line, providing independent assurance that risk management and governance processes are working effectively.

Risk Register

The risk register is a tool used to track and manage risks. It records details about each risk, including its impact, likelihood, and the measures in place to mitigate it. By maintaining an up-to-date risk register, organizations can prioritize actions and ensure a consistent approach to managing risks.

Risk Appetite

Risk appetite is the amount and type of risk an organization is willing to take in order to achieve its objectives. It reflects the organization's willingness to accept uncertainty and the extent to which it seeks out risk. The firm's risk appetite guides decision-making and risk management practices.

Crisis Management

Crisis management involves preparing for and managing incidents that could severely disrupt the business. This requires having plans and teams in place to deal with unexpected events such as a significant cybersecurity breach or a natural disaster. Effective crisis management can limit the damage and help the organization to recover more swiftly.

BCP/DR (Business Continuity Planning/Disaster Recovery)

Business Continuity Planning (BCP) and Disaster Recovery (DR) are closely linked aspects of ERM that focus on sustaining business functions in the face of significant disruption and returning to normal operations as quickly as possible.

- Business Continuity Planning: Involves identifying key products or services and the most urgent activities that underpin them and planning how the business will continue to deliver these in the event of a crisis.

- Disaster Recovery: Focuses on restoring data access and IT infrastructure essential for delivering the critical activities of the firm.

Enterprise Risk Management is a cornerstone of modern business resilience, especially in cybersecurity. It involves a proactive approach to identifying, assessing, managing, and monitoring risks. By understanding and applying the principles of ERM, businesses can better navigate the unpredictable landscape of cyber threats and protect their core operations against a wide variety of risks.

Frameworks and Standards in Cybersecurity

Choosing the right frameworks and standards is crucial for establishing a strong cybersecurity posture. These frameworks and standards provide organizations with structured approaches to manage cyber risks, enhance security, and respond effectively to incidents. The Map of Cybersecurity Domains by Henry Jiang offers a detailed categorization of these vital components. Let's explore some of the most prominent ones detailed in the framework:

NIST Cybersecurity Framework

The NIST Cybersecurity Framework was developed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology to offer a comprehensive set of voluntary guidelines, best practices, and recommendations for organizations to manage cybersecurity-related risks. The Framework is adaptable to various sectors and is designed to foster risk and cybersecurity management communications amongst both internal and external organizational stakeholders. Its core functions—Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, and Recover—create a strategic view of the lifecycle of an organization's management of cybersecurity risk.

MITRE ATT&CK Framework

The MITRE ATT&CK Framework is a globally-accessible knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques observed from real-world cyberattacks. "ATT&CK" stands for Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge. Security teams use this framework to better understand security risks, improve threat detection, and enhance their incident response strategies. It assists in planning security improvements and verifying defenses against common adversarial behaviors.

ISO 27001 Framework

The ISO 27001 Framework is an international standard that provides the specification for an information security management system (ISMS). It helps organizations in any sector keep information assets secure. Adopting ISO 27001 helps your company manage the security of financial information, intellectual property, employee details, and information entrusted by third parties. It involves a systematic examination of information security risks, threats, vulnerabilities, and impacts, and the design and implementation of a coherent and comprehensive suite of information security controls.

OWASP TOP 10 (WebApp & API)

The OWASP TOP 10 is a standard awareness document for developers and web application security. It represents a broad consensus about the most critical security risks to web applications. Project members include a variety of security experts around the globe who have shared their expertise to produce this list. Additionally, the OWASP TOP 10 for API Security focuses on the specific threats and vulnerabilities related to APIs, which are becoming increasingly vital in today's interconnected software ecosystem.

CIS TOP 20 Controls (CIS Benchmarks)

The CIS TOP 20 Controls are a prioritized set of best practices designed to provide actionable ways to stop today's most pervasive and dangerous cyberattacks. Developed by the Center for Internet Security (CIS), the CIS Benchmarks are recognized globally as industry best practices for securing IT systems and data against the most pervasive attacks. These controls are effective precisely because they are derived from the most widespread attack data, vetted across a very broad community of government and industry practitioners.

Frameworks and standards in cybersecurity are instrumental in helping organizations implement effective security measures. They are a testament to the collaborative effort of experts and industry leaders to confront cybersecurity challenges head-on. By employing these frameworks and standards, organizations can align their cybersecurity strategies with industry best practices, ensuring both the integrity of their operations and the trust of their stakeholders.

Security Operation in Cybersecurity

Security Operation constitutes the heartbeat of an organization's cybersecurity defenses, where continuous monitoring, threat detection, and response actions take place. In Henry Jiang's Map of Cybersecurity Domains, we see how Security Operation encompasses several key activities that work in concert to protect digital estates. Let's dive into the dynamic field of Security Operation and explore its integral components.

Vulnerability Management

Vulnerability Management is a proactive approach to managing cybersecurity risks. It involves identifying, classifying, prioritizing, remediating, and mitigating vulnerabilities within an organization's systems. Here's how it works:

- Identification: Tools and processes are used to discover existing vulnerabilities in software and hardware.

- Classification and Prioritization: Once identified, vulnerabilities are categorized based on their severity, and the risk they pose to the organization is assessed.

- Remediation and Mitigation: The most critical vulnerabilities are addressed first, either by applying patches, making configuration changes, or implementing workarounds.

- Continuous Monitoring: Regular scans and assessments ensure that new vulnerabilities are found and managed promptly.

Through effective vulnerability management, organizations can drastically reduce the windows of opportunity that attackers might exploit.

Threat Hunting

Unlike automated detection systems, Threat Hunting is a forward-looking process that involves human expertise to identify hidden threats that evade traditional security measures. Threat hunters proactively sift through networks and datasets to:

- Detect Anomalies: Uncover irregular patterns of behavior that could indicate malicious activity.

- Hypothesis Generation: Craft potential threat scenarios based on current trends and known tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs).

- Investigation and Analysis: Examine network and system events to confirm or dismiss the hypotheses.

- Continuous Improvement: Use findings to enhance existing security processes and tools.

Threat Hunting is critical for organizations to stay ahead of sophisticated and emerging threats.

Security Operation Center (SOC)

A Security Operation Center or SOC serves as the central hub for monitoring and analyzing an organization's security posture on an ongoing basis. Key functions of a SOC include:

- 24/7 Monitoring: Keeping a vigilant watch over networks, servers, endpoints, applications, and other systems to detect unusual activities.

- Event Analysis: SOC analysts evaluate security alerts to determine their severity and potential impact.

- Coordination and Escalation: Ensuring that identified threats are dealt with promptly and efficiently, escalating to the appropriate teams when necessary.

- Continuous Improvement: Updating defense measures and playbooks based on the latest intelligence and emerging threats.

A SOC is the embodiment of an organization's commitment to cybersecurity vigilance.

SIEM/SOAR

Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) and Security Orchestration, Automation, and Response (SOAR) tools are at the forefront of technological aids for Security Operations.

- SIEM: Combines comprehensive data collection, normalization, analysis, and reporting capabilities to provide real-time visibility into an organization’s security landscape.

- SOAR: Enhances the effectiveness of SIEM by automating routine tasks, orchestrating complex workflows, and enabling swift response to incidents.

Together, SIEM and SOAR technologies supercharge the capabilities of security teams, allowing for more efficient operation and faster reaction times.

Incident Response

Incident Response is a structured approach to handling and mitigating cybersecurity incidents. It typically involves:

- Preparation: Developing and maintaining a comprehensive incident response plan.

- Detection and Analysis: Identifying and investigating potential security incidents.

- Containment, Eradication, and Recovery: Neutralizing threats, removing infected elements, and restoring systems to normal operation.

- Post-Incident Activities: Analyzing the incident to improve future response efforts and prevent similar occurrences.

Effective incident response minimizes the damage of security breaches and swiftly restores operations.

Active Defense

Active Defense strategies aim to outmaneuver adversaries by making it more difficult for them to succeed in their attacks. This involves:

- Deception Technologies: Employing decoys and honeypots to distract and mislead attackers.

- Adaptive Perimeter Defenses: Dynamically adjusting defenses in response to perceived threats.

- Threat Intelligence Sharing: Collaborating with other organizations and entities to share information about current threats and attacks.

By deploying Active Defense measures, organizations can create a dynamic and hostile environment for cyberattackers, reducing their chances of success.

The domain of Security Operation is a multifaceted battlefield where organizations must constantly evolve their strategies to guard against an ever-changing threat landscape. By investing in Vulnerability Management, embracing Threat Hunting, establishing a robust SOC, utilizing SIEM/SOAR technologies, implementing a solid Incident Response framework, and adopting Active Defense measures, organizations can fortify their cyber defense and maintain resilience against potential cyber threats.

Threat Intelligence in Cybersecurity

In the age of vast cyber threats, organizations must stay ahead of potential security breaches by leveraging an effective threat intelligence strategy. This vital area of cybersecurity focuses on gathering and analyzing information about current and potential attacks that threaten the safety of an organization's digital assets. Henry Jiang's Map of Cybersecurity Domains spotlights threat intelligence as a key player in the grand scheme of cybersecurity. Let's dive into the internal and external aspects of threat intelligence.

External Threat Intelligence

The external component of threat intelligence revolves around collecting and evaluating information from outside the organization. This intel originates from different sources and serves as an early warning system to defend against cyber threats before they impact the organization.

Contextual Intelligence

Contextual intelligence is the process of understanding cyber threats within the broader context of your industry, existing security posture, and the motivations of threat actors. It transforms raw data into actionable insights by considering factors such as the source of the threat, techniques used, targets, and potential impact on business operations. Here's how contextual intelligence can enhance an organization's defense mechanisms:

- Industry Trend Analysis: Understanding the types of attacks that are most common or rising within a specific industry can prepare an organization to defend against them effectively.

- Threat Actor Profiling: Knowing the adversaries targeting your sector and their methodologies can tailor your cybersecurity measures accordingly.

- Geopolitical Insights: Global events and trends can influence the cyber threat landscape. An awareness of these dynamics aids in predicting and contextualizing threats.

Incorporating contextual intelligence means that organizations aren't just reacting to threats; they're anticipating them through a lens grounded in relevance to their specific circumstances.

Internal Threat Intelligence

The internal side of threat intelligence looks at the data originating from within the organization to identify indicators of compromise or suspicious activities that could suggest an imminent threat. It's about using internal resources to pinpoint vulnerabilities before they are exploited by external or internal actors.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

IOCs are pieces of forensic data, such as system log entries or files, that suggest a network intrusion or potential security incident. Recognizing IOCs helps in detecting breaches early to limit damage. Examples include:

- Unexpected Outbound Traffic: Suggestive of data exfiltration or communication with command-and-control servers.

- Unusual User Behavior: Could signify an account takeover or insider threat activity.

- Suspicious File Modifications: Often a sign of malware or a persistent threat actor’s presence.

Routine monitoring for IOCs is a proactive measure in identifying and managing threats before they escalate into larger-scale incidents.

Intelligence Sharing

When organizations share intelligence with each other, they empower a collective defense strategy. Intelligence sharing allows for the collaborative analysis of threats and helps organizations learn from the experiences and encounters of others. This can take place in several forms:

- Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs): Sector-specific centers that provide a central resource for gathering and sharing information on cyber threats.

- Cross-Industry Platforms: Tools and services that enable companies across different sectors to share intelligence securely and in real-time.

- Private-Public Partnerships: Collaborations between government entities and private organizations to enhance the national cybersecurity posture.

Each approach promotes a collaborative environment where the latest intelligence is circulated, thus enriching an organization's internal defenses and enriching its risk assessment capabilities.

Threat intelligence, in its dual external and internal capacities, acts as the eyes and ears of an organization's cybersecurity fortress. By leveraging a blend of contextual insights, recognizing IOCs, and participating in intelligence sharing, organizations can craft a more dynamic and informed security strategy to face the cyber challenges of today and tomorrow.

Application Security

Application security is a critical component of a robust cybersecurity posture, ensuring that software applications are not just functional but also secure from potential threats. Applications, whether they are used internally by businesses or offered as services to customers, are frequent targets for cyberattacks. Leveraging the detailed insights from Henry Jiang's Map of Cybersecurity Domains, let's break down the integral aspects of application security that organizations must focus on.

S-SDLC (Secure Software Development Lifecycle)

The Secure Software Development Lifecycle (S-SDLC) is a process that incorporates security at every step of software development. This approach is crucial for preempting vulnerabilities rather than addressing them after deployment, which can be costlier. Key elements of S-SDLC include:

- Threat Modeling: Identifying potential threats early in the development process.

- Security Requirements: Defining security criteria that software must meet.

- Secure Code Review: Regularly reviewing code for security issues during development.

- Security Testing: Conducting rigorous testing to detect and fix security flaws before release.

By integrating these security practices, developers can create safer applications that are resilient to cyber threats.

Security UX

User Experience (UX) encompasses all aspects of the end-user interaction with the company, its services, and its products. When discussing Security UX, we refer to the design of security features that are both robust and user-friendly. Security measures should never hinder user experience; they must be intuitive to ensure that users will adhere to security protocols. For example:

- Two-Factor Authentication (2FA): It adds an extra layer of security but should be implemented in a manner that is simple for users to set up and use.

- Password Recovery: Systems must balance security and usability to assist users who have forgotten their credentials without compromising the account's integrity.

Security QA

Security Quality Assurance (QA) involves the systematic monitoring and evaluation of the various aspects of a project, service, or facility to maximize the probability that minimum standards of quality are being attained by the production process. Key practices include:

- Vulnerability Assessments: Regularly scanning the applications for known vulnerabilities.

- Penetration Testing: Simulating cyberattacks to discover exploitable weaknesses.

- Code Reviews: Checking for coding errors that could lead to security breaches.

Security QA aims to identify flaws early, thereby avoiding the costs and reputational damage of a security incident post-deployment.

API Security

With the increasing use of Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) to enable software systems to communicate, securing APIs has become paramount. Effective API security requires methods such as:

- Authentication and Authorization Controls: Ensuring that only legitimate users and systems can access APIs.

- Input Validation: Preventing malicious data from entering through an API.

- Encryption: Securing data in transit between services.

Securing APIs prevents unauthorized access to backend systems and protects data integrity and availability.

Source Code Scan

Source code scanning, also known as static application security testing (SAST), examines source code for security vulnerabilities. Automated tools can detect issues such as:

- Injections flaws: Like SQL or XML injection, where untrusted input can control application behavior.

- Buffer Overflows: Causes when an application writes data beyond the boundaries of pre-allocated memory buffers.

- Cross-Site Scripting (XSS): Occurs when an application includes untrusted data in a web page sent to a browser.

By scanning source code before it is compiled, organizations can fix vulnerabilities early in the development process.

Data-Flow Diagram

Data-flow diagrams (DFDs) provide a visual representation of the flow of data through an application system. They help in the analysis and design stages by clarifying:

- Data Processing: How data is processed at various stages within the system.

- Data Storage: Where and how data is stored, providing insight into potential security vulnerabilities.

- Data Interactions: How data moves between different components of the system, which can help trace the origins of data breaches.

Creating comprehensive DFDs allows security professionals to identify potential security lapses and ensure proper controls are in place to safeguard sensitive data within applications.

By paying careful attention to these domains of application security, organizations can significantly improve the security posture of their software offerings. Ensuring that applications are developed and maintained with security in mind protects against data breaches and builds trust with users. Application security is not a one-time goal but an ongoing commitment to safeguarding the digital landscape from evolving threats.

Cybersecurity Risk Assessment

Risk assessment is a vital component of any cybersecurity strategy, involving the identification, evaluation, and prioritization of risks. It enables organizations to apply resources strategically to the areas of highest concern. Henry Jiang's Map of Cybersecurity Domains outlines critical areas to focus on during risk assessment activities. Let’s dive into them one by one for a clearer understanding.

Assets Inventory

The first step in risk assessment is identifying what you're protecting—an organization’s assets inventory. Assets are not just physical items like computers or servers, but also software, data, intellectual property, and even the organization’s reputation. By maintaining a detailed inventory, organizations gain visibility into what needs protection and can prioritize efforts accordingly. An assets inventory should include:

- Hardware and Software: Listing all physical devices and applications within the organization.

- Data: Classifying data types from sensitive customer information to proprietary business data.

- Digital Infrastructure: Mapping out network components and cloud resources.

Knowing what and where your assets are is paramount in the fight against cybersecurity threats.

3rd Party Risk

Today’s business ecosystems are interlinked with vendors, suppliers, and third-party service providers, each with varying degrees of access to one’s business data. Recognizing the risks associated with these external parties is crucial. To mitigate 3rd party risk, organizations should:

- Conduct Due Diligence: Before partnering with a third party, assess their security posture.

- Regularly Review Contracts: Ensure contracts include clauses that enforce data protection.

- Monitor Third-Party Practices: Regularly evaluate the security practices of partners to ensure ongoing compliance.

This continuous scrutiny helps safeguard against vulnerabilities that could be exploited via an external party’s systems.

Risk Monitoring Services (Risk Score)

Risk monitoring services, often reflected in a risk score, provide a quantitative measure of an organization's cybersecurity posture. This score is typically calculated by:

- Data Breach History: Analyzing past incidents to identify patterns or recurring vulnerabilities.

- Security Measures: Evaluating the effectiveness of current security practices and defenses.

- Industry Benchmarks: Comparing risk posture against industry peers.

Organizations can use risk scores from these services not only to gauge their own security strengths and weaknesses but also to evaluate the risk that partners or suppliers might represent.

Vulnerability Scan

A vulnerability scan is the cybersecurity equivalent of a regular health check-up. It’s an automated process that searches for known vulnerabilities within an organization's network, systems, or applications, covering:

- Software Flaws: Identifying out-of-date software or systems missing critical security patches.

- Configuration Errors: Detecting settings that may leave a system open to unauthorized access.

- Security Weaknesses: Finding gaps in defenses before cybercriminals do.

Regular scans keep organizations informed about where they may be susceptible to attacks, enabling timely preventative measures.

Penetration Testing

Penetration testing, or "pen testing," goes a step further than vulnerability scanning. It's an authorized simulated cyberattack performed to evaluate the effectiveness of security controls, involving:

- Ethical Hackers: Skilled professionals who think like attackers and test the system's defenses.

- Real-World Scenarios: Mimicking the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) used by real adversaries.

- Post-Test Analysis: Providing insights into the breach points, extraction of data, and how long intruders might remain undetected.

Penetration tests offer actionable information on how an organization can improve its security postures, such as fixing vulnerabilities and tightening access controls.

Risk Assessment in cybersecurity is about knowing your weak spots and taking pre-emptive action. It involves a deep dive into the assets that make up the backbone of an organization, understanding the risks posed by external entities, continuously monitoring the cyber health of the entity, and actively searching for weaknesses with the intent to fortify them. Employing these practices allows organizations to develop a dynamic and robust cybersecurity strategy, effectively reducing the risk and impact of cyber threats.

Conclusion

The cybersecurity domains are the critical pillars supporting the vast and dynamic field of cybersecurity. By understanding and mastering these domains, professionals can better prepare for and respond to the numerous threats that organizations face in the digital age.

As technology continues to advance, so too will the complexity of the cybersecurity landscape. Professionals in the field must remain vigilant, continuously learning and adapting to protect against an ever-evolving array of cyber threats. Whether you're a seasoned expert or a newcomer to the field, an understanding of these domains is crucial to anyone involved in cybersecurity.